‘The Limit is Past the Sky’ for Ph.D. Student Seeking Extraterrestrial Life

Kenzie Mounir (G’30) is used to having to explain astrobiology to others. More often than not, she’s met with blank stares.

An interdisciplinary field that interweaves astronomy, biology, chemistry and geology, astrobiology is the study of life in the universe. Astrobiologists study if the processes and resources that sustain survival on Earth are present on other planets and search the cosmos for biosignatures, or evidence of life, to understand how and where life may exist elsewhere.

Kenzie Mounir (courtesy of Kenzie Mounir)

“Jupiter’s moons have whole oceans on them that we haven’t explored,” Mounir said. “That’s something that a lot of people don’t really picture when it comes to space, thinking about oceans or atmospheres that look anything like Earth’s. Earth is a very special planet that ended up being this perfect harbor for human life, and astrobiology helps us understand our place in the solar system.”

“The limit is past the sky” in this discipline, Mounir said, and her interplanetary studies are rocketing forward at Georgetown. This fall, she started her doctorate in the Department of Biology through the Patrick Healy Graduate Fellowship, a merit-based program that supports students who may not otherwise be able to pursue a Ph.D.

“I’m glad to be joining a wonderful cohort of people who study such different things,” said Mounir.

Cairo and Space Chemistry

Mounir was born in Cairo, Egypt, and immigrated with her family to Cleveland, Ohio, when she was 7 years old.

Everything was different in Ohio for Mounir and her family, from the language and culture to the weather and landscape. Mounir learned to embrace the quirks of life on a new continent and make connections within her new community as she adapted to her new environment. She soon found that Cleveland’s temperate climate and suburban sprawl, though worlds away from Cairo’s desert air and bustling city, started feeling like home.

Living in these distinct settings was an early lesson in how life in one location can parallel that in another, despite different circumstances. This philosophy lies at the foundation of astrobiology, where researchers investigate, for example, how the same life-sustaining elements and minerals produced by seismic activity on Earth’s seafloors came to be found in rocks on Mars.

Mounir brought that open-minded approach with her to Washington University in St. Louis, where she enrolled as a chemistry major before her interests gravitated toward space.

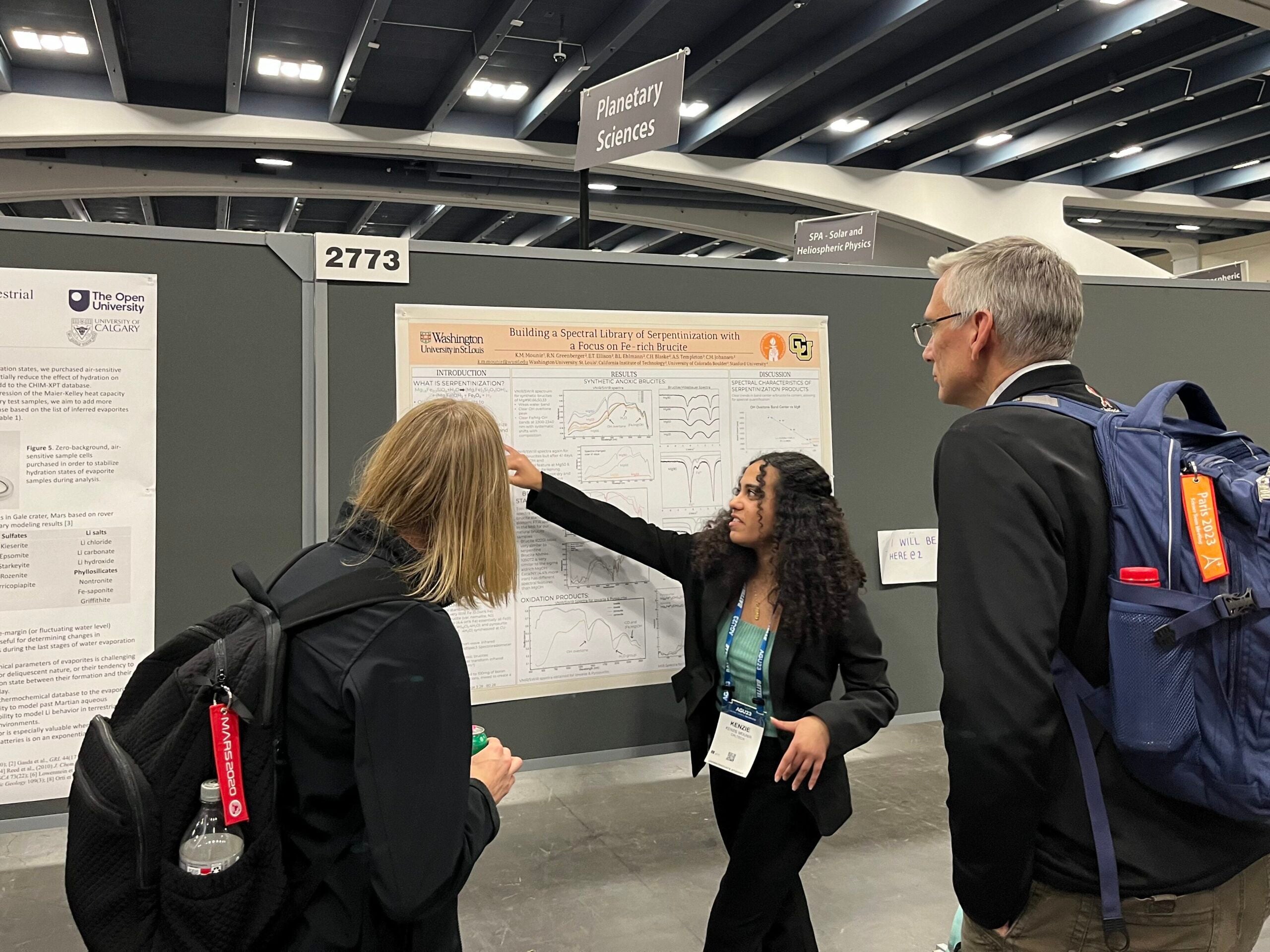

Mounir presents a research poster at the 2023 conference for the American Geophysical Union (AGU), an earth and space science society. (Courtesy of Kenzie Mounir)

“I took a first-year seminar called, ‘Habitable Planets,’ and I learned there were people studying the chemistry of space,” Mounir said. “I was like, ‘That’s so cool! Let me do that.’”

Moon Dust Meditations

At Washington University, Mounir majored in planetary science and minored in biology. In her sophomore year, she was named a MARC U-STAR Fellow, a research training program for students who are underrepresented in the biomedical sciences, through the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

Throughout college, Mounir followed her interest in the natural sciences through opportunities in the U.S. and abroad. She conducted geologic field research on the island of Hawai’i through an earth, environmental and planetary science class, completed a geochemistry internship at the California Institute of Technology and studied abroad in Dublin, Ireland, at Trinity College, along the way gaining new mentors who encouraged her curiosity.

“Every person has a lesson to offer you. I think that’s the same thing that I’m doing with disciplines: taking all these different fields and putting them together as these pieces of a larger puzzle.”

Kenzie Mounir

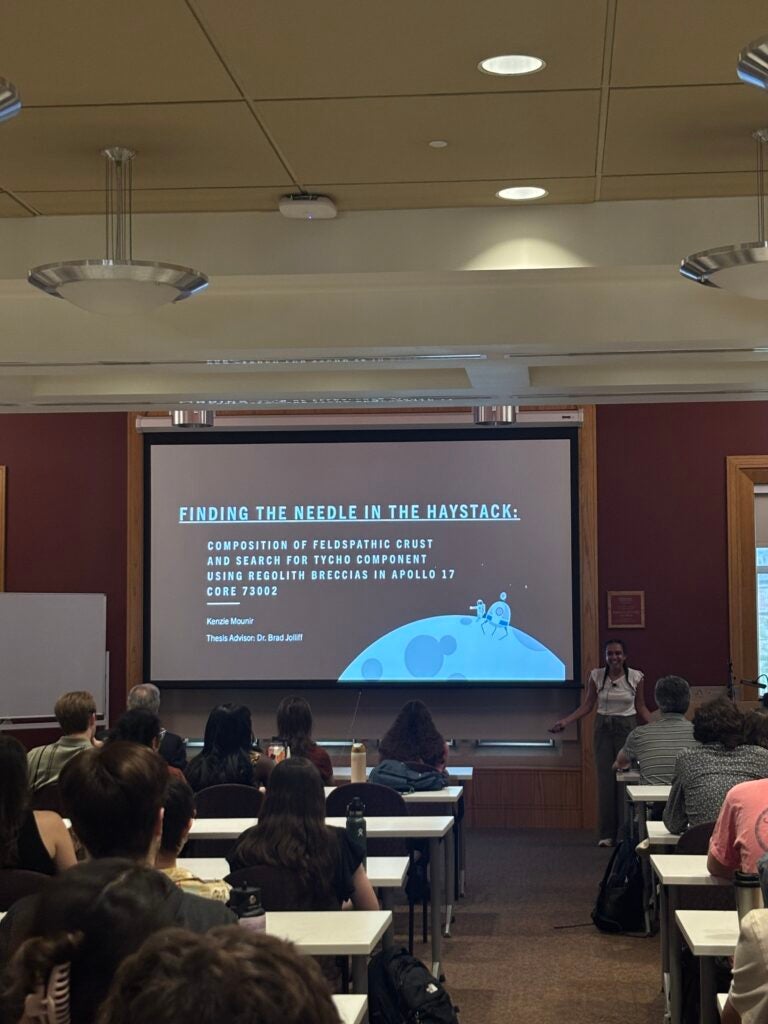

Mounir spent her senior year in a university lab attempting to trace the geologic history of the moon by analyzing samples of lunar rock and regolith — mineral material often called moon dust — gathered during the Apollo 17 mission in 1972.

Mounir’s team mapped the mineral content of materials from the moon’s Taurus-Litrow Valley, a basin deeper than the Grand Canyon, and unexpectedly found concentrations of elements consistent with those in rocks ejected from the Tycho Crater, over a thousand miles away. Their work opened the door to further studies of the moon’s landscape and lunar exploration.

“Everybody looks at the moon and thinks, ‘It all looks the same,’” said Mounir, who graduated with her bachelor’s in May. “But it actually has such different mineral groupings that come from different places. Each specific mineral can tell you more about the evolution of the moon.”

With geologic insight and a high-tech electron probe, Mounir was learning how to use tiny fragments of rock to answer big questions about the solar system. She wanted to continue this type of research and sought Ph.D. programs in astrobiology.

Shooting for the Stars

Washington, DC, attracts space scholars for its proximity to NASA facilities, including the NASA Headquarters in Washington, DC, and the Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. When Mounir learned that Professor Sarah Johnson’s Biosignatures Lab collaborates closely with the flight center and NASA’s Network for Life Detection, she was sold.

“Her research fit perfectly in terms of what I wanted to do, and I really liked how multidisciplinary it was — she doesn’t look at just one planet or just one technique, she looks at all different spectrums,” Mounir said.

Mounir is still determining her research focus at Georgetown but is excited to learn more about biosignatures through Johnson’s lab. Johnson said she is “over the moon” to have Mounir join her research group.

Mounir presents her senior thesis to members of the Washington University in St. Louis’ Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences this spring. (Courtesy of Kenzie Mounir)

“She brings with her an outstanding record of scientific achievement and a genuine passion for discovery that will enrich our entire community,” Johnson said. “I have no doubt that she will make significant contributions to the field of planetary science. She has an exceptionally bright future ahead!”

The present is just as stellar for Mounir, who said she is honored to contribute to Georgetown’s interdisciplinary focus through the Healy Fellowship. She was also recently named a recipient of the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program, which recognizes students “with exceptional potential for leadership in research and innovation.”

Mounir said she’s also looking forward to working with undergraduates as a teaching assistant, the first step in an anticipated career in academia, and getting to know the people who make up her new home.

“When I visited Georgetown this spring, I saw families out with their strollers, grandparents walking their dogs and somebody studying on a park bench,” she said. “All these different people in the same place shows that DC has so much to offer.”