HIV Has Devastated Her Home. She’s Pursuing a Ph.D. to Channel Aid Where It’s Needed

When public health advocate Martha Cameron (G’25, G’30) speaks about the importance of HIV/AIDS awareness and aid, her mind and heart go to Zambia.

She thinks of her loved ones and the generations of Zambians lost to the disease in a country where nearly 10% of the population aged 18-49 has HIV and limited access to pre-exposure and antiretroviral therapies.

When Cameron speaks about HIV, she speaks with authority. Cameron, from Lusaka, Zambia, has lived with the disease for 22 years and built a globe-spanning career in HIV awareness.

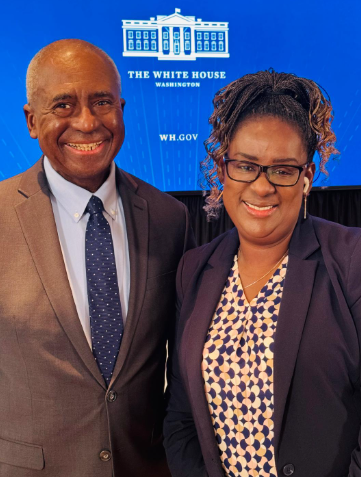

Cameron, then-vice chair of the People Living with HIV Caucus, poses with Ronald Johnson, chair of the group, at an HIV Quality of Life Symposium at the White House. (Courtesy of Martha Cameron)

She has continued her advocacy at Georgetown. Cameron joined the Georgetown University Medical Center in 2023 as a research specialist to study the disease’s effects on women, and she returned to school last fall via the M.S. in Global Infectious Disease program.

This August, she starts her Ph.D. in global infectious disease at the School of Health through the Patrick Healy Graduate Fellowship, a merit-based program that supports students who may not otherwise be able to pursue a Ph.D.

For Cameron, getting to this point has been a faith-based journey — one which she nearly abandoned. She always told herself that if she didn’t start her doctorate by age 50, she would give up the dream.

Her Ph.D. program starts two months shy of her 51st birthday.

“This has just been such an incredible thing to be able to do now as a capstone not just for my education but for my life,” Cameron said.

Finding a Passion for Public Health

While in college in Lusaka, Cameron studied education, English and French. She pictured herself becoming a lawyer like her mother, Lucy Banda-Sichone, a civil rights activist and the first female Zambian Rhodes scholar.

Then her mother died while Cameron was taking her final exams.

Though Banda-Sichone was never diagnosed with HIV, Cameron said, her death occurred amid a surge of the HIV epidemic in Africa. Many of Cameron’s colleagues lost their parents around the same time to the disease, and Cameron started wondering why.

“This was always a question for me: What happened to my country?” Cameron said. “What was it that we did wrong? I had no understanding of public health, of health disparities, of poverty.”

Cameron spent the next few years working at nonprofits, including Every Orphan’s Hope, where she met women and children widowed and orphaned by HIV. Cameron’s drive to help people affected by the epidemic was grounded in her strong Catholic beliefs and intensified when she was diagnosed with AIDS, HIV’s final stage, in 2003.

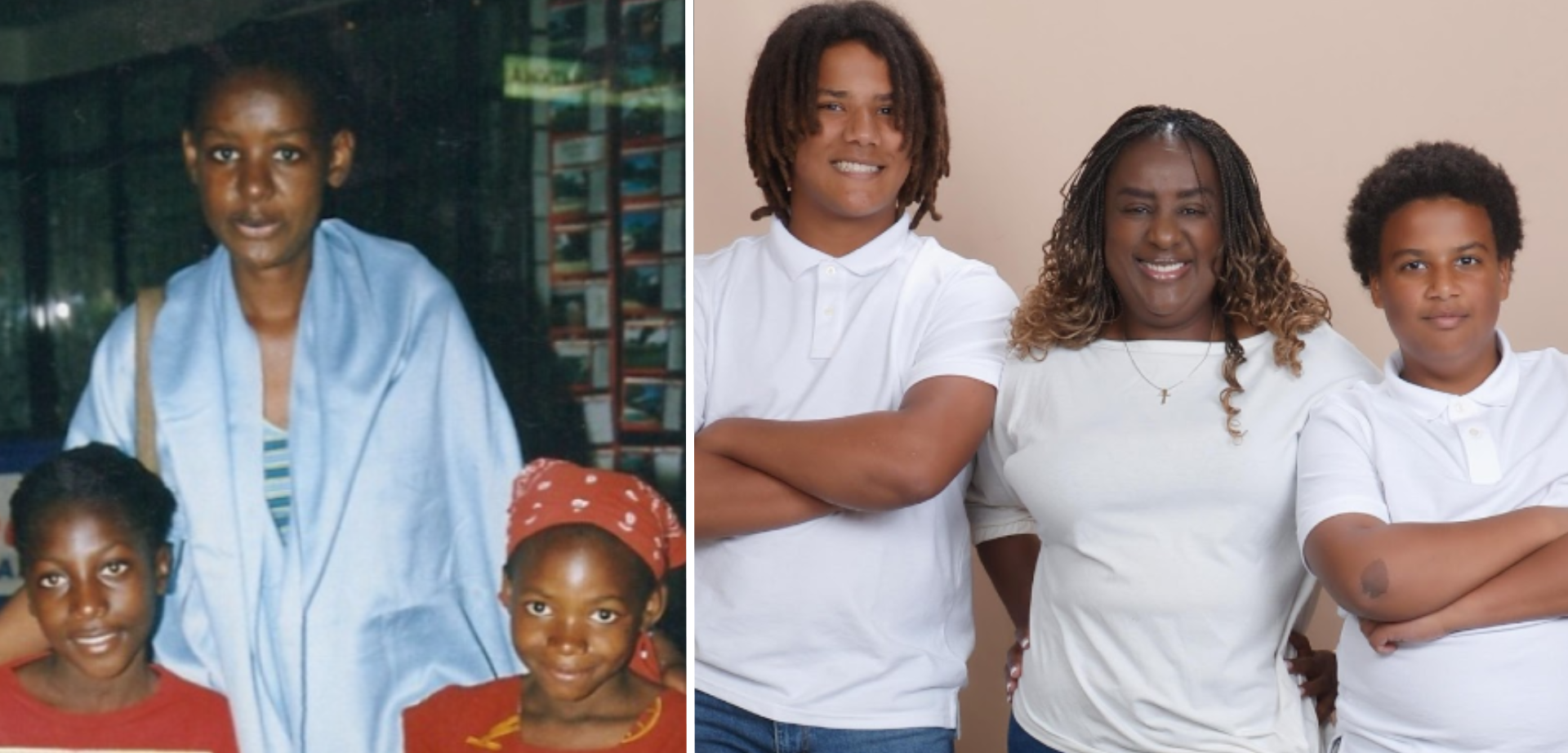

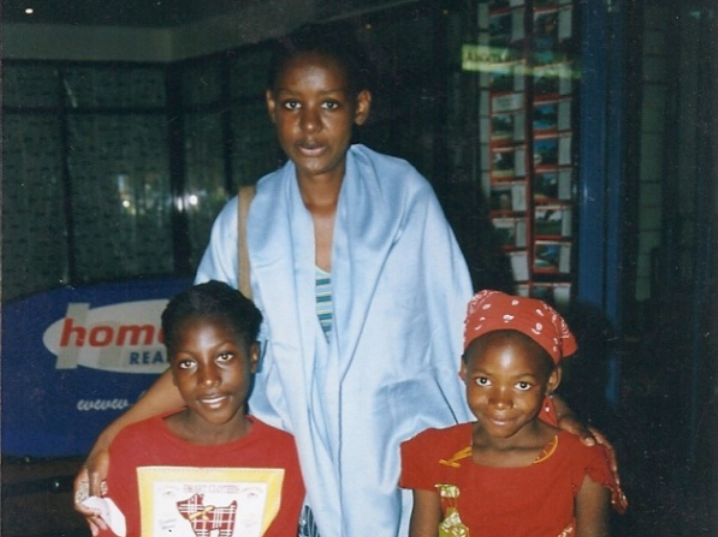

Cameron working with orphans in Zambia in 2003. She was diagnosed with AIDS that year. (Photo courtesy of Martha Cameron)

Cameron was fortunate to be one of the first recipients of antiretroviral therapy (ART) through PEPFAR, the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. Her health recovered through treatment and she fully dedicated herself to HIV awareness and prevention.

Over the next two decades, she held leadership roles in organizations including The Women’s Collective, Children’s AIDS Fund International, the National Working Positive Coalition and The International Community of Women Living with HIV North America (ICW-NA).

Along the way, she moved to Leesburg, Virginia, with her husband, earned a Master of Public Health from Walden University and had two sons, both of whom were born HIV-negative thanks to ART.

Cameron said her health and that of her children, now ages 14 and 16, demonstrate the life-changing effects of HIV/AIDS research.

“It was very public, my HIV diagnosis,” Cameron said. “I was very visibly sick, and many people knew that. So many people who see me now and see the children sometimes don’t even believe they’re my children.”

A desire to advance medicine that helps families like hers led Cameron to Georgetown in 2023.

“The role that I’m most proud of is being a mother,” Cameron said. Her sons, Josiah and Judah, are now 16 and 14. Cameron also has an older adopted daughter, Tamar (not pictured), who is 29. (Photo courtesy of Martha Cameron)

Learning and Questioning

For two years, Cameron has worked on the Study of Treatment and Reproductive Outcomes in Women (STAR) team at Georgetown University Medical Center. This longitudinal research studies reproductive-age women living with HIV to understand and improve this group’s health, along with that of their families and communities.

The project is supported by the National Institutes of Health and conducted in collaboration with university hospitals across the South. Seeing how this work uplifts HIV-positive women reminds Cameron how transformative the investment of national, state and local stakeholders in public health research can be.

Equipped with additional advocacy and research experience, Cameron decided to pursue a master’s in global infectious disease at Georgetown last fall. She aspired to better understand the systems and policies that dictate why and how aid is distributed to communities in need.

Through classes like Interdisciplinary Perspectives in Infectious Disease, Cameron learned how various epidemics and corresponding aid responses from global partners have shaped public health. She learned to think about outbreak response in socioeconomic and political terms.

“It was a fire hose of information from real practitioners, people who had been there,” Cameron said. “None of these classes are theoretical. You learn and question.”

Cameron, far right, speaks at a panel commemorating PEPFAR’s 15th anniversary in 2018. Also presenting at the panel was Dr. Anthony Fauci, then-director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Both Cameron and Fauci are now at Georgetown, with Fauci serving as a Distinguished University Professor in the School of Medicine and the McCourt School of Public Policy. Sitting between Cameron and Fauci is Dr. Mark Dybul, a creator of PEPFAR and a current professor at the Georgetown University School of Medicine. (Photo courtesy of Martha Cameron/Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation)/

Cameron is pursuing a Ph.D. on the same subject to continue learning and questioning. She chose Dr. Babatunji Oni as her advisor for his expertise in building health infrastructure in Africa and the Caribbean, and because he challenged her to think beyond her own experiences, Cameron said.

Oni, a senior program director of Georgetown’s Center for Global Health Practice and Impact, said Cameron is an ideal global health scholar as she relates her life and work to her studies and uses them to spur her pursuit of knowledge.

“I have witnessed firsthand her intellectual curiosity, striking insightfulness and most of all her genuine passion for the welfare of those most affected by infectious disease around the world – especially due to inequity or lack of access to care,” Oni said. “I am very much honored to be her mentor and look forward to continuing this journey with her.”

For someone who once doubted her potential as a non-traditional Ph.D. candidate, Cameron has big plans for the future.

She hopes to research effective strategies to expand HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment infrastructure in Africa, particularly at home in Zambia. As U.S. legislators reevaluate the future of aid programs like PEPFAR, Cameron recognizes an opportunity to approach aid as a tool to empower countries to grow their own resources.

After all, Cameron said, she is proof of what these programs can do.

“I’m alive because of science, and I’m alive because the federal aid got to Zambia when it did,” she said.